I’m standing at a hospital bedside in a black suit and flared trousers. Beneath my NHS-issued face mask there’s a comical look on my face, like someone whose insides have been kicked out.

I’m gripping the pallid-grey knuckle of my father’s hand and listening to his shallow breaths, as the ventilator shifts in time to the gentle rise and fall of the sheet across his chest.

I remind myself this is not a memory I wish to keep but I know I will keep it all the same.

His wife is begging him not to go but here, now, I am only a witness.

I speak to him through my thoughts, beyond the sedatives and the impossible depth of sleep which separate us.

‘If you have to leave,’ I say. ‘If it’s harder to stay, then it is to go. Then go.’

Sometimes it’s better not to hold on.

Before it happened, I would have believed losing my father would have been unbearable but in reality, amidst the clatter of day-to-day life, the event was not what the anxious mind fantasised. In truth, we cannot imagine the mundane rituals that accompany these moments. There is a bureaucracy to it, a method of managing the grief as you try to remind yourself to eat and sleep, to smile when spoken to. Or to stop when needed.

We live and we die, such is life.

My oldest friend left me without any need of words. I had said everything I needed to whilst he was still alive. For that I am grateful.

The last thing my father would ever say to me was, “Don’t worry about me, Ben. I’m fine. I’ll see you soon.”

The last thing I would ever say to him was,”for Christ’s sake, call me if you get ill.”

He didn’t.

I don’t know if that’s funny but it at least has the structure of something that should be funny.

My mother and I dig small hole at the grave of my grandparents. His ashes are dense and heavy like sand and the colour reminds me of oatmeal. It bothers me to think of the bones of his fingers, ground down to dirt. He used to work with his hands.

We bury him there, marked by a marble plaque I’ve ordered off the internet. We can’t afford a headstone.

If I had been alone, there would have been no words but my mother says a few.

If there had been money enough, I would have forgone the experience altogether. I am not a gravedigger nor did I ever wish to be one. Why should I dig his grave? Why should I have to make these decisions?

In the days before, his ashes trouble my mother. She burns incense daily. Shrouds it with flowers.

It’s during lockdown and so he arrives in a box like an Amazon delivery. I’m holding him before I realise what it is I’m holding. The weight reminds me of a newborn.

Burying him isn’t a legal act, but it is a necessary one.

My father is a kind man. Trained as an engineer, in love with vintage cars and motorcycles, he dismantles anything that breaks, whether it gets put back together or not. That is a lesson he tried to teach me. Anything broken can be fixed.

It can’t. But it’s still worth trying anyway.

As a child he would sleep late and often lose his temper when disturbed, regretting his actions later. He’s not angry at us but at the things around him. Things he breaks and then later tries to fix. Life feels hard on him, or rather he takes it hard. He probably has depression, though in those days, no one would quite know to diagnose him.

He tells me when older, that nothing in his life had ever worked out the way he had hoped. Years later, I think of my own life. What is the story we will tell ourselves? Is that the story we want our lives to be about? That nothing worked out, or that we never gave up?

I have many dreams after his passing. In one, I am still a boy and my father comes to me holding a small animal in his hands, a squirrel, wounded and dying. He talks to me about losing his own father. He tells me the body is a machine, and that one day it simply ceases to function.

I know the memory from which it has flowered. I’m thirteen, sitting on the floor of our garage, crying over the bodies of my pet rabbits. I was lonely as a child and they were my closest friends.

The sun is low, creeping in through the trees as my father digs a hole to bury them in. Their bodies are still soft and furred but beneath, they are cold and hard as clay.

My fathers sits with me and tells me that the rabbits are gone, that their bodies were only ever just a shell, and now the thing that made them what they were, has left.

He tells me it is okay to be sad but that nothing can hurt them anymore.

I will think of this many times when he’s gone.

In another time, my father is in overalls. Beams and bricks are stacked against the back of my childhood home. An extension is built by my father and the man he apprenticed to, Charlie – the dead and the long time dead. It’s nothing fancy; a small conservatory which extends from the kitchen, but this is the thing that will destroy us.

This is long ago, before I was born, in another time. Here, my father is young, he builds his house, he works to make a family. Charlie is a kind man, his friend. when he dies, it breaks my father’s heart. My father tells me that Charlie used to repair pocketwatches in his spare time, spending his evenings in an old shed at the end of the garden. After he dies, his wife and my father will find hundreds of empty whiskey bottles beneath it, all posted through a gap in the floorboards.

I will probably be about twelve when we lose our house. Bought by my grandfather, in a time when property was to be lived in, not rented for profit. It is sold to pay for debts, stripped by bailiffs, long-since fallen into disrepair. It makes barely a dent in the money owed.

My father tells me not to walk on the conservatory roof, he says its not strong enough. I climb out of second floor windows and parkour before parkour was ever something you could google. I can get from the second story window to the back garden in seconds.

This is how I evade capture.

The bailiffs are a familiar sight at our door, along with teachers and education officers. I am notoriously truant, in love with my childhood, with this home. In love with the music, films and books, the toys and possessions. Why would I leave?

Sometimes the teachers physically drag me to school, kicking and screaming. Surely that wasn’t legal.

In my child’s brain, I mirror my family’s battle, I am Joeseph K, I am Woody Guthrie. This machine kills fascists. To me the bailiffs, the teachers, the education officers are all the same - the machine that consumes us.

My father tells me when I’m older that he didn’t mind that I didn’t go to school, he thought it showed character. This this statement will define me.

My grandmother takes out a loan, one with an interest rate so high it can never be paid. She takes it out to build our conservatory. She takes it out but tells no one. Years later, the figure owed is unrecognisable, unpayable.

My father gets legal aid, there were no witnesses to the signing but no one cares.

This will cost us dearly.

What money made from the house is quickly swallowed by solicitors and landlords. No school will take me because I’m blacklisted for truancy, so I get sent to a boarding school. These are the terms and conditions. The education officer at this time is kind, my mother tells me he quits his job over me - is that true? I don’t know. He tells me that schools would rather take the most troublesome students instead of me, I just make their attendance figures drop. I wish I knew his name.

I’m sent to psychiatrists, to official buildings with clinical hallways where my future is dissected. The officer argues for home education but all I am told is that it is my duty. I overhear him saying to my mother ‘it’s always the clever ones that don’t want to go.’ Always the clever ones?

Surely better to be clever?

The house is empty. Everything seems to happen so quickly, within weeks we are leaving. Did we know, or was I simply not told?

When the furniture is moved, we find a hole in the plasterboard, covered by the headboard of my parents bed. We didn’t know it was there. Something about it sticks in my mind – this fist-sized crevice that was there all along, pale and crumbling, revealed by the turmoil of a broken home. Our house, in ruin.

The soft evening light crawls across my bedroom wall as my family empty the rooms. I stare at it and feel the deepest sadness for the passing day. Everything is unspoken in this moment. I remember an early thought. Our time. Do we create it, or do we consume it?

A passage from one of my father’s books: ‘The day is over, but is my life over? I ask midnight’s mournful toll.’

I’m an only child. At fifteen I have no friends. Those I had, have left for university, and that seems like a world I cannot enter. I have no GCSEs, I have no means of getting them. I am wild and I am strange. I have been so divorced from the world of normal people’s lives, that it now terrifies me.

I sit with my father in late night cafes. They are filled with strangers with no homes to go to. This is the last stop before the streets and so everyone sits, nursing cold cups of tea.

At night my heart aches with loneliness and I cannot sleep. I walk the streets until the sun breaks the clouds. I long for a human voice. I haunt the old house where I grew up, walking past it daily. I wonder if some part of our family remains inside, some fragment of better days.

I like the city. I like how the lighted shop windows can make you feel as though life could return. You can imagine the sound of people here. Picture their faces.

I hope I’m never this alone again.

We live in the countryside until the money runs out. We don’t have hot water or electricity, some days we don’t even have food.

When there was no fuel in the car, my father would walk into town. Its eight miles to the nearest shop. It takes all day if you want to top up the electric key meter. We sell what we have to make enough money for food. Some nights, I sleep with a towel balled against my stomach to stop it aching.

Sometimes I walk with my father but I’m still a boy and I can’t keep pace. I can see it hurts him when we have to sell anything that belongs to me. Old toys, a model railway.

One day, the car finally breaks down. My father slams his fist into the dashboard over and over until his hand is bleeding. Then he bows his head against the wheel and begins to cry.

He says my mother has left him. I don’t know what to say.

A few minutes pass and he gently pulls back the air vent.

We never speak of it again.

We are evicted. The rent is long overdue and my mother comes to help us move. I’m not going with my father. She has a house in Exeter where I can live with her. My father and grandmother are considered ‘voluntarily homeless’ by the council and as such will be temporarily housed in a B&B whilst their case is assessed.

They are moved to The Osprey guesthouse in Exeter, where they share a tiny room. The place is filthy and filled with rats. The room above holds a family of four with two children. A young mother in the building complains of rats getting into her baby’s cot. Many of the residents are drug addicts. It is 2001. Exeter council, a Labour seat.

I meet my dad each day in a cafe on Sidwell Street. He saves up to buy me a Christmas present. It costs fourteen pounds. It never seems to stop raining, and the air is cold. His hair is turning white now.

I often dream of the rain slick streets, my father at my side, always at night. I fear the other people there, they are killing each other. Crowds, rioting and fighting as they beat each other to death in the streets. Somehow my father finds us safe passage amongst them. I don’t let go of his hand.

My grandfather died when my father was young. He tells me how he had visited him in hospital after a heart attack. My father had plans to go to the cinema but when he tried to cancel them, my grandfather told him to go and have a nice evening.

“You’ll be okay though?” my father asked him.

“No, not this time…,” my grandfather replied. “But look after your mother for me.”

Later that night, my father is coming back from the cinema and is he suddenly becomes aware that my grandfather is dead. And he’s right.

My father tells me later that he honestly believed his old man didn’t care. It was just one of those things. Such is life.

My grandmother says ‘drechtly’ and speaks in a thick Devonian accent. She cooks fried breakfast in lard and leaves cigarette ash in the egg yolks. My mother paints flowers on walls and my father makes model airplanes.

By the time the house is gone, my grandmother is eighty years old and a letter tells her she will be homeless in two months. I’m sixteen years old now. If I could find the people that did this; the loan sharks, the solicitors, the council workers – I would kill them all. I would kill them for killing us.

I feel injustice and I feel angry.

At home, I’m rarely spoken to as a child. I’m told about the civil rights movement when I’m too little to understand, I’m read Kafka and Herman Hesse. I listen to cassette tapes on a Walkman as I fall asleep and the songs are Leonard Cohen or Simon and Garfunkel. The lyrics paint deep images in my mind, shaping my dreams. When I play with toys, I am the camera. Surrounded by music, films and literature, I want the world to be a work of art.

I want to be a work of art.

I can sheathe a katana and jump from upper story windows. I am free and I am full of dreams. School by comparison feels childish and dull, my world is full of artists and philosophers, people who pushed the boundaries. I have nightmares of Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, see fragments of Werner Herzog’s Aguirre in my daydreaming and above all things, want to be a Ghostbuster.

A small side-room contains dad’s collection of vinyl. The gatefold pop-up sleeve of Jethro Tull, Emerson Lake and Palmer’s robot dinosaurs artwork. My dad tells me about Vincent Van Gough as we listen to Don Maclean. He explains the lyrics to me. The Sargents are The Beatles, the Jester is Bob Dylan, the king is Elvis Presley.

He teaches me that words are more than than just words - they are doors and they are windows.

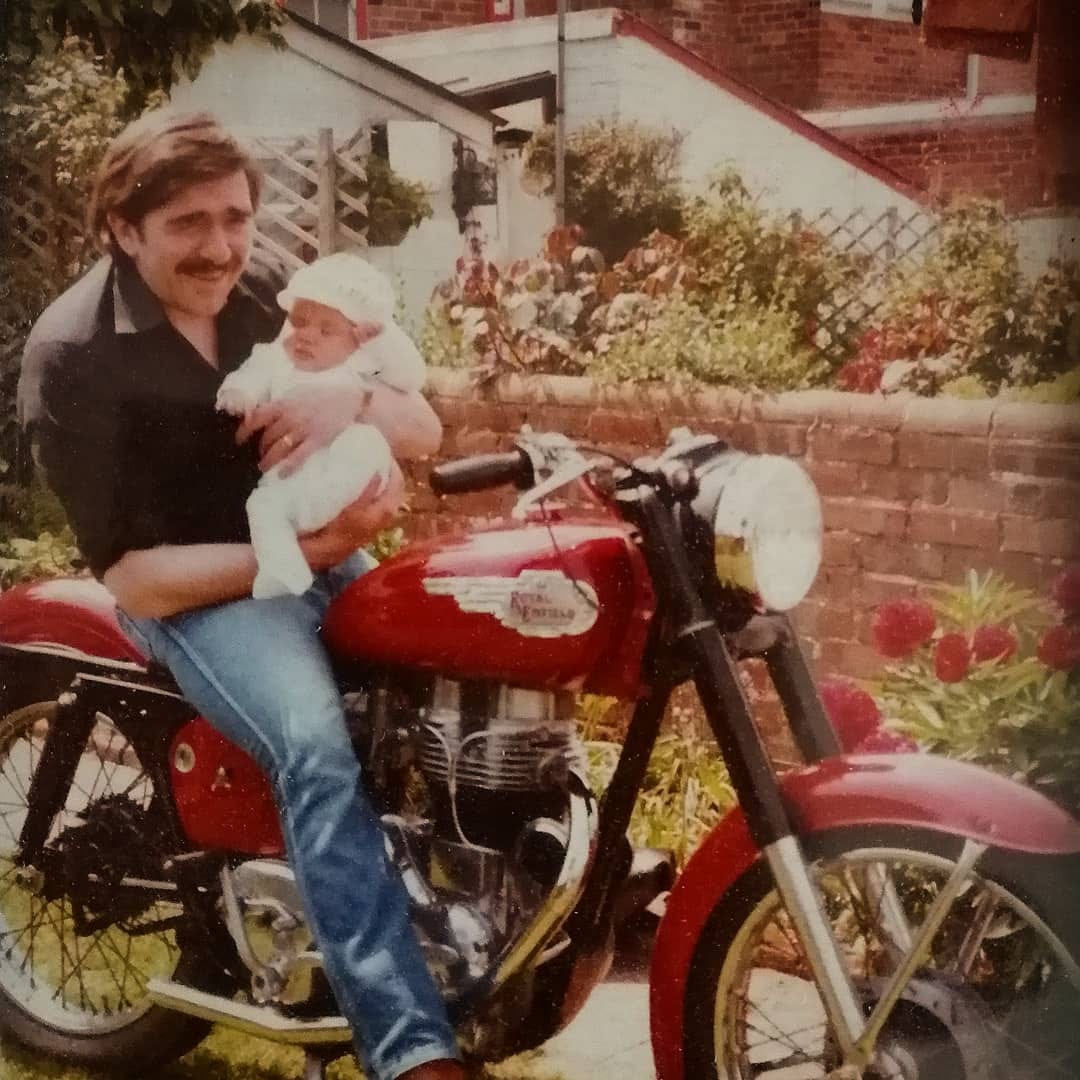

My mother puts his picture in a frame. It appears on my shelf two days after he’s gone. In it, he cradles a baby in his arms and his legs slung across a Red Royal Enfield motorbike.

The baby in the photo is me and the smile he has is real.

My father sits in the library each day. He reads the law books, writing down notes. He writes to the council, he writes to the papers but it’s something in between that does it. He sends the council a draft of a story for the press, it mentions all the council workers names names and tells how they are making an eighty year-old woman homeless, one month before Christmas.

They get offered a house.

My father is older now, and he’s remarried. My grandmother dies.

I see her the week before and she complains that her rings won’t fit on her fingers anymore. She says she can hear music playing from upstairs all day long, the same song over and over.

I can’t hear it at all.

We used to go out or day trips but she’s gotten too frail now. She can still read the papers without glasses and tells me stories about the people she once knew.

I say, “I’ll see you soon.” When I leave.

And she says, “I hope so.”

She’s ninety-two and dies in the night whilst reaching to pull on her slipper.

“That’s the end of that,” my father says, though not unkindly.

I think of this when he goes.

Before it happened, I would have believed losing my father would have been unbearable but nothing is unbearable. We either survive it or we don’t - the suffering is only momentary.

The doctor asks me what my father would want – his body is now beyond repair. I don’t realise it then but as I trawl through his council house, uncovering photos of better times, I realise that something had changed. If we don’t participate in our own lives, we can die many deaths.

My father withdrew from life. The bailiffs, the barristers, and the education officers all took their toll. The unpaid water bills, the court summons, the endless threats. Is this how you kill a person?

Defeated in spirit; my oldest friend. Angry at government, angry at Brexit, the hedge-funders, the Tax Dodgers, the Gary Barlowes, the Tim Martins. Angry at Exeter City Council, or the back-handed housing contracts, the brown envelopes passed to universities, the nets that cleeve the toes off birds, and the spikes that stop rough sleepers.

He told himself that there was nothing he could do, and so he didn’t He told himself he wanted to be left alone, and so he stopped.

I’m at a corporate do and Roy Slack, the same councillor whose administration tried to make my father homeless, talks about supporting theatre. I can’t bring myself to applaud – I know the size of his expense account. I watch him drinking the complimentary ale.

I use a shovel to clear the last of my father’s possessions. They’ve rotted into compost. I don’t know what they ever were. My grandmother’s clothes perhaps.

The doctor asks me what my father would want and I tell him that I don’t want them to keep him alive for us. I trust his opinion. He says he thinks we’re not doing him any service by keeping him alive, and so I agree to let him go.

I’m not with him when it happens. I remember him telling me not visit my gradmother after she was gone. ‘Remember her when she was alive,’ he told me.

He’s so deeply sedated, he doesn’t feel a thing. I think of the end of Ride The High Country and the dying gunfighter: “I don’t want them to see this, I’ll go it alone.” He says.

My father loved that film. He wouldn’t want me to watch him die.

The doctor asked me what my father would want but I’ll tell you what I didn’t tell him.

He wants people not to suffer, to not live in a world where people take the jobs that bring others misery. He’d want them not to not kick people from homes, or send out debt collectors to threaten them in the night. He would want people’s lives to not be fodder for the profit of big business, or for our survival to be seen as a means for profit. He’d want for for taxation that makes the rich howl in agony. Or for those that take to stormy seas in tiny rubber boats to find dry land.

He’d say:

“Cool-Hand-Luke the parking meters, bring pitchforks to the utility shareholders and land barons, make them flee from their second homes.

To hell with the fat cats, the CEOs, the celebrity mansions, the rituals of the crown. To hell with those that buy and sell us.

Damn those that kick down. Make them feel the shame. Make them cower behind their giant gates and pray for forgiveness for being so vain.”

My father is dead. I look at the ocean. The sun is out.

There are children playing in the tide as seagulls wheel through the azure blue above. I am with my best friend and my father is dead.

A flower now is no less beautiful, than in a world where he was alive. The sun is no colder, and the air is no less sweet.

Life is perfect as it is.

I am grateful for the conversations, for the friendship. I am grateful that he did not suffer, and I am grateful he didn’t know the end was close to hand.

I hang my grandfather’s barometer on the wall, and my childhood seems so close I can almost touch it.

I leave the hospital and I know I won’t speak with him again.

He dies and I am certain he no longer exists.

I feel no ghostly presence no sense of being watched.

I feel awake.

A leaf arches its back against the sun. A flower grows. A blade of grass stands tall, then recedes into the earth.

A crooked tree is no less a tree than the one that grows straight.

We are told our life is a story. We build our narrative and we set our goals. But a river is a river, and a tree is a tree. We live and we die.

It is fine.

We speak about success but in doing so, we create failure. We are forged in a system that tells us to be judged or to meet expectations set by system that is no more a part of this world than the feudal lords of old.

We expect it is right to suffer. We feel guilt in being alive.

A boy goes to sleep but before he can do so, he must think of those he loves - his friends, his family, the animals he cares for. He fixes them in his mind and bids them each a goodnight.

He wants to be good and he wants to be kind . He wants to be smart enough to not do foolish or unkind things.

What kind of man will he become?

Time to turn back and descend the stair, With a bald spot in the middle of my hair— (They will say: “How his hair is growing thin!”)

An aged man is but a paltry thing...

Is it all dismantled? That house, my home, my childhood?

The bricks and mortar still exist but what occupies that now?

What wasn’t done, must be accepted. No more worth in it now, than it will have in the future.

We must learn to break bread with those we love and that which is still amongst us.

We must remember to cherish the things that still remain.

We whisper a mantra:

’All is well.’

Bruce Springsteen plays as the rain thunders down on a silver Ford Granada. My father smokes cigarettes through a crack in the window, his sleeve glistening with rain.

I’m just a boy but we are together, a family. The wolf is at the door but it is not yet in the house. At that moment, the world beyond the glass crawls with water. My father smiles.

I will think of this, years from now.

A flower is no less beautiful, in a world where I don’t exist.

Thank you.

What a moving piece of writing. I'm reading it on Father's day and now I'm going to call my Dad. Time flashes by. Reading this took me back - I could almost smell the past. It's a reminder to be more present around the people we love. It's sad that in these fast paced times we need to be reminded. Thanks for sharing your story. It was so impactful for me.